KABUL – Afghanistan’s current rulers are maintaining a careful balancing act in their relationships with regional militant groups, according to a new academic study that sheds light on how ideological alignment, economic interests, and old alliances continue to shape the country’s post-2021 security landscape.

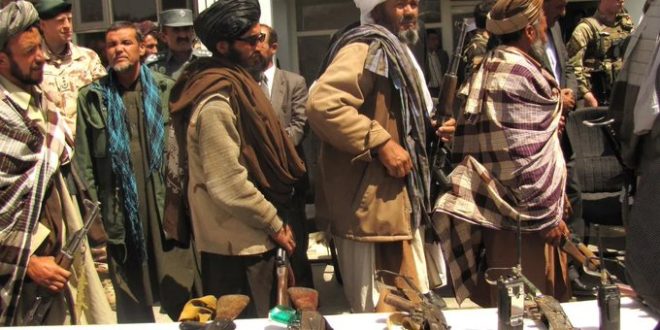

The research, led by Dr. Weeda Mehran of the University of Exeter, describes how local and transnational armed groups—including Al-Qaeda, Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), the Islamic Jihad Union (IJU), and the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM)—have increasingly relied on the Taliban’s approval to operate within Afghan territory. Since coming to power, the Taliban has shifted from being dependent on these groups for military and logistical support to asserting control over their activities, while avoiding open confrontation.

The study finds that this shift has not severed the deep ideological and personal bonds that link these groups. Instead, these connections are being maintained and, in some cases, leveraged for strategic advantage. Cooperation has become more transactional—based on mutual benefit, including shared revenues from natural resources and access to smuggling routes—while ideological alignment continues to underpin the relationships.

According to the study, Al-Qaeda has established training centers, madrassas, and recruitment networks inside Afghanistan, all under a tacit understanding with the current leadership. The group is reportedly generating tens of millions of dollars weekly from gold mines in the north, with a portion of the profits funneled to the ruling administration—income not reflected in official budgets. Meanwhile, smuggling routes once used to finance the insurgency are now enabling the trafficking of drugs, weapons, and other contraband through joint efforts.

Experts say these arrangements have broader regional implications. TTP, for instance, has used its sanctuary in Afghanistan to regroup and intensify cross-border attacks in Pakistan’s tribal areas. In return, it maintains close ties with Taliban commanders, including through intermarriages and the acquisition of Afghan documents.

Despite the shift in power dynamics, the study emphasizes that the Taliban remains reluctant to challenge these groups directly. This restraint, researchers argue, helps preserve unity among fighters and avoids sparking internal divisions. At the same time, it allows Afghanistan’s rulers to benefit from these networks—technically, financially, and strategically—without appearing to compromise national authority.

“Cooperation between the Taliban and these groups has evolved, but it remains resilient,” Dr. Mehran said. “The Taliban’s control has increased, but ideological and personal ties have kept the door open for collaboration. This has serious implications for regional and global security.”

The report suggests that while the Taliban no longer depends on groups like Al-Qaeda in the way it once did, it continues to derive strategic benefits from allowing their presence—a calculated approach that sustains influence across the region while limiting direct engagement.

Afghanistan Times

Afghanistan Times